The Crete of Richard M. Dawkins (1903-1919)

Who was R.M. Dawkins?

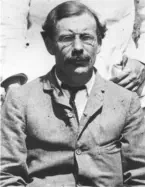

Richard MacGillivray Dawkins (1871-1955) first went to Crete in 1903 to work as a prehistoric archaeologist. He took part in excavations at various Minoan sites on the island for several years. During this time he became more interested in medieval and modern Crete than in its prehistoric past. Later he went on to become Bywater and Sotheby Professor of Byzantine and Modern Greek Language and Literature at the University of Oxford (1920-1939), where he was also a fellow of Exeter College.Dawkins’ Crete book

In 1916-19, during and immediately after the First World War, Dawkins served in Crete as an intelligence gatherer in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. During this period he began planning and writing a book about the medieval and early modern buildings of Crete (especially churches and monasteries), as well as topography, communications (mule tracks and roads), botany and folk traditions, legends, and beliefs. In addition, he describes various traditional crafts and the implements and mechanisms associated with them: keeping bees, milling flour, pressing oil from olives and extracting salt from saltpans. Dawkins also describes the curious practice of wiping bundles of leather straps over a certain species of shrub in order to gather a kind of gum used for making incense – a practice that is still being carried out near the village of Sises where Dawkins observed it – and even combing the gum from the beards of goats that graze amongst the bushes. Dawkins never completed his planned book, but left drafts of all of the 32 chapters, which are arranged geographically from west to east.What was happening in Crete at that time?

Dawkins was in Crete during a critical period in the island’s history. When he first went there in 1903, Crete was an autonomous state that had recently emerged from more than two centuries of Ottoman rule. It was still under the suzerainty of the Sultan but under the protection of Britain, France, Russia and Italy. At the time when Dawkins was there, the population consisted of both Christian and Muslim Cretans. In 1908, Christian Cretans declared de facto Union with Greece, but the island’s incorporation into the Greek state was not internationally recognized until 1913. In the early 1920s, after Dawkins had finally left the island, all the Cretan Muslims were deported to Turkey in exchange for Greek Christians who had been deported from Turkey. Dawkins witnessed the process of modernization that gathered pace after Crete was incorporated into the Greek state. This entailed not only the building of new roads, but the demolition of Venetian city walls along with the fine ornamental city gates.What does the Dawkins Crete material consist of?

The material published here consists primarily of the incomplete drafts of the 32 chapters of Dawkins’ proposed book. In collaboration with his wife, Jackie Willcox, Peter Mackridge, retired Professor of Modern Greek in the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, has edited Dawkins’ drafts and added notes of his own providing elucidations, corrections and background material as well as comparing Dawkins’ descriptions with the situation today. The material contains photographs from Dawkins’ archive, together with a much larger number of photographs that Peter has taken himself to illustrate Dawkins’ text. Crete has changed tremendously since Dawkins was last there in 1919. Huge material damage and loss of life were inflicted by the German occupiers of Crete in 1941-45, including whole villages such as Anogia, Kandanos, Gerakari razed to the ground, not to mention many fine Venetian buildings in Hania destroyed by German bombs in May 1941. In more recent decades, mass tourism, road building and the construction of new buildings have altered Cretan life irrevocably. In the process Cretans have become much more prosperous. Dawkins’ material presents an invaluable picture of Crete before these changes took place. But if you travel to Crete and look closely, you find that a lot of what Dawkins described is still there: churches and monasteries (some in a better state than they were a century ago), medieval castles, Venetian fountains, all too few mule tracks, but even some individual trees as well as other plant species (Cretan dittany and Cretan tulips) that are still growing in exactly the same spots where Dawkins describes them. He identifies some fascinating Ottoman buildings that have since been repurposed and survive to this day, and he reveals why the flesh parts of the ancient white marble male figure who features on the Bembo fountain in Herakleion used to be covered in black paint. Author: Peter MackridgePeter Mackridge M.A., D.Phil. Professor of Modern Greek (12 March 1946 - 16 June 2022)

Peter joined the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages as Lecturer in Modern Greek in 1981. He was Professor of Modern Greek from 1996 until his early retirement in 2003. His research interests covered various areas in Greek language, literature and cultural history since AD 1100, but he specializes in the period since 1750. The recent focus of his research was the language and content of Greek literature 1700-50, that is, immediately before the rise of Greek nationalism. His other interests included the history of the Greek language, Greek language ideologies, and the history of Greek cultural nationalism, but also aspects of poetry such as versification. His translations of stories by the 19th-century authors Vizyenos and Papadiamandis and a collection of haikus by the 21st-century poet Haris Vlavianos were published in 2014-15. Peter was an editor of the journal Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies and a member of the editorial board of the Greek journal Kondyloforos. He was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Athens in 2008 and an honorary professorship at the University of the Peloponnese in 2017. Source:Faculty of Medieval & Modern Languages, University of Oxford

Richard MacGillivray Dawkins

BSA Portrait

Peter Mackridge at the Gennadius Library, Athens.

Photograph: Cathy Cunliffe

Crete has a rich and varied history and we are sure that many of you will find this rare glimpse by

Richard Dawkins into this wonderful Island a pleasure to read. It is with special thanks to the Faculty of

Medieval & Modern Languages, University of Oxford for giving their permission to offer you the

opportunity to read this work by Peter Mackridge.

.webp)

.webp)

The Crete of Richard M. Dawkins (1903-1919)

Who was R.M. Dawkins?

Richard MacGillivray Dawkins (1871-1955) first went to Crete in 1903 to work as a prehistoric archaeologist. He took part in excavations at various Minoan sites on the island for several years. During this time he became more interested in medieval and modern Crete than in its prehistoric past. Later he went on to become Bywater and Sotheby Professor of Byzantine and Modern Greek Language and Literature at the University of Oxford (1920-1939), where he was also a fellow of Exeter College.Dawkins’ Crete book

In 1916-19, during and immediately after the First World War, Dawkins served in Crete as an intelligence gatherer in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. During this period he began planning and writing a book about the medieval and early modern buildings of Crete (especially churches and monasteries), as well as topography, communications (mule tracks and roads), botany and folk traditions, legends, and beliefs. In addition, he describes various traditional crafts and the implements and mechanisms associated with them: keeping bees, milling flour, pressing oil from olives and extracting salt from saltpans. Dawkins also describes the curious practice of wiping bundles of leather straps over a certain species of shrub in order to gather a kind of gum used for making incense – a practice that is still being carried out near the village of Sises where Dawkins observed it – and even combing the gum from the beards of goats that graze amongst the bushes. Dawkins never completed his planned book, but left drafts of all of the 32 chapters, which are arranged geographically from west to east.What was happening in Crete at that time?

Dawkins was in Crete during a critical period in the island’s history. When he first went there in 1903, Crete was an autonomous state that had recently emerged from more than two centuries of Ottoman rule. It was still under the suzerainty of the Sultan but under the protection of Britain, France, Russia and Italy. At the time when Dawkins was there, the population consisted of both Christian and Muslim Cretans. In 1908, Christian Cretans declared de facto Union with Greece, but the island’s incorporation into the Greek state was not internationally recognized until 1913. In the early 1920s, after Dawkins had finally left the island, all the Cretan Muslims were deported to Turkey in exchange for Greek Christians who had been deported from Turkey. Dawkins witnessed the process of modernization that gathered pace after Crete was incorporated into the Greek state. This entailed not only the building of new roads, but the demolition of Venetian city walls along with the fine ornamental city gates.What does the Dawkins Crete material consist of?

The material published here consists primarily of the incomplete drafts of the 32 chapters of Dawkins’ proposed book. In collaboration with his wife, Jackie Willcox, Peter Mackridge, retired Professor of Modern Greek in the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, has edited Dawkins’ drafts and added notes of his own providing elucidations, corrections and background material as well as comparing Dawkins’ descriptions with the situation today. The material contains photographs from Dawkins’ archive, together with a much larger number of photographs that Peter has taken himself to illustrate Dawkins’ text. Crete has changed tremendously since Dawkins was last there in 1919. Huge material damage and loss of life were inflicted by the German occupiers of Crete in 1941-45, including whole villages such as Anogia, Kandanos, Gerakari razed to the ground, not to mention many fine Venetian buildings in Hania destroyed by German bombs in May 1941. In more recent decades, mass tourism, road building and the construction of new buildings have altered Cretan life irrevocably. In the process Cretans have become much more prosperous. Dawkins’ material presents an invaluable picture of Crete before these changes took place. But if you travel to Crete and look closely, you find that a lot of what Dawkins described is still there: churches and monasteries (some in a better state than they were a century ago), medieval castles, Venetian fountains, all too few mule tracks, but even some individual trees as well as other plant species (Cretan dittany and Cretan tulips) that are still growing in exactly the same spots where Dawkins describes them. He identifies some fascinating Ottoman buildings that have since been repurposed and survive to this day, and he reveals why the flesh parts of the ancient white marble male figure who features on the Bembo fountain in Herakleion used to be covered in black paint. Author: Peter MackridgePeter Mackridge M.A., D.Phil. Professor of Modern Greek

(12 March 1946 - 16 June 2022)

Peter joined the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages as Lecturer in Modern Greek in 1981. He was Professor of Modern Greek from 1996 until his early retirement in 2003. His research interests covered various areas in Greek language, literature and cultural history since AD 1100, but he specializes in the period since 1750. The recent focus of his research was the language and content of Greek literature 1700-50, that is, immediately before the rise of Greek nationalism. His other interests included the history of the Greek language, Greek language ideologies, and the history of Greek cultural nationalism, but also aspects of poetry such as versification. His translations of stories by the 19th-century authors Vizyenos and Papadiamandis and a collection of haikus by the 21st-century poet Haris Vlavianos were published in 2014-15. Peter was an editor of the journal Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies and a member of the editorial board of the Greek journal Kondyloforos. He was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Athens in 2008 and an honorary professorship at the University of the Peloponnese in 2017. Source:Faculty of Medieval & Modern Languages, University of Oxford

Richard MacGillivray Dawkins

BSA Portrait

Peter Mackridge at the Gennadius Library,

Athens. Photograph: Cathy Cunliffe

Crete has a rich and varied history and we are sure that many of

you will find this rare glimpse by Richard Dawkins into this

wonderful Island a pleasure to read. It is with special thanks to

the Faculty of Medieval & Modern Languages, University of

Oxford for giving their permission to offer you the opportunity to

read this work by Peter Mackridge.

.webp)

.webp)